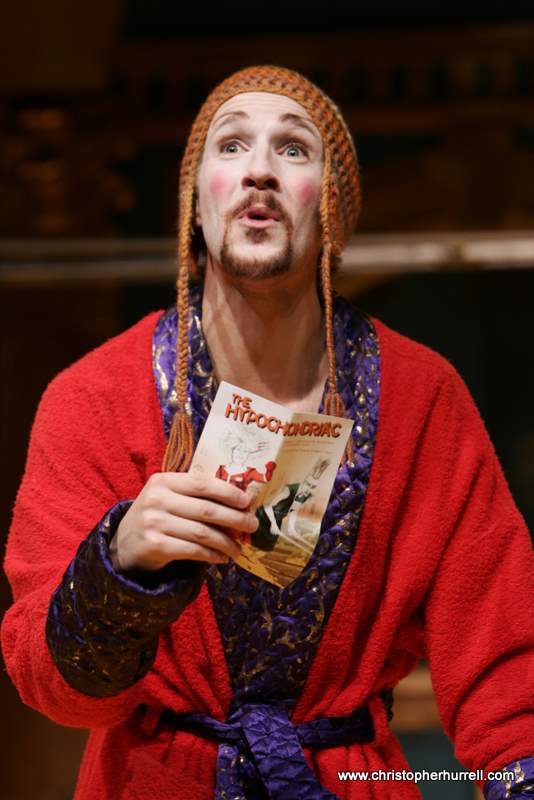

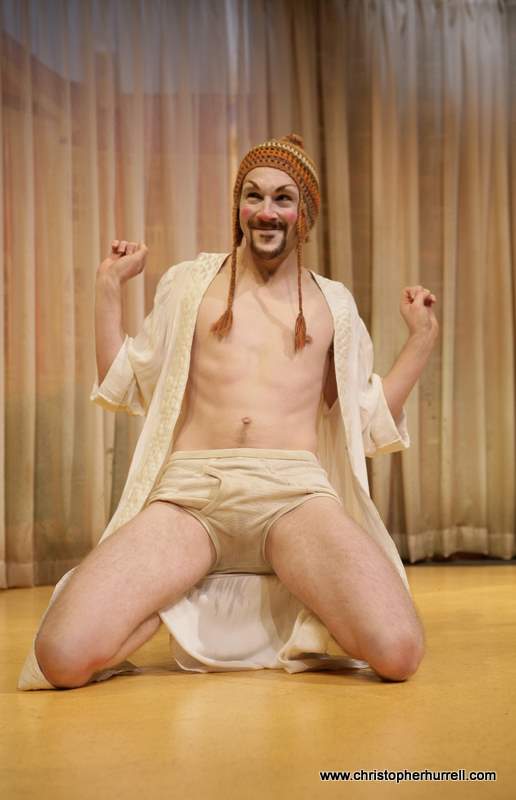

The Hypochondriac

National Institute of Dramatic Art

Sydney 2010

Based on Molière's La Malade Imaginaire

Argan

Samuel O’Sullivan

Beline

Silvina D’Alessandro

Toinette

Katherine Moss

Angelique

Jenny Wu

Thomas/Fleurant

Alan Chambers

Diafoirhoea / Bonnefoi / Purgon

Gabriel Fancourt

Beralde

Nadim Kobeissi

Cleante/Louison

Guy Simon

Director

Christopher Hurrell

Designer

Pia Leong

Lighting Designer

Chantelle Foster

Production Stage Manager

Benjamin Northmore

Costume Supervisor

Zoe Gymer-Waldron

Deputy Stage Manager/Sound Operator

Sarah Stait

Lighting Operator/Head Electrician

Nicholas Payment

Assistant Stage Manager

Katie Hankin

Lighting Assistant

Natalie Smith

Lighting Crew

Olivia Benson

Costume Assistant

Katrina Mcfarlane

Costume Assistant

Sophie Cameron

Tailor

Monica Smith

Tailor

Rebecca Jones

Movement

Lisa Minnett

Voice

Jane Harders

Sound Designer

Jeremy Silver

Properties Supervisor

Govinda Webster

Properties Assistant

George Buchannan

Properties Assistant

Meg Roberts

Scenery Construction

Govinda Webster

Scenery Construction

Terry Roy

A black comedy about the irresistible nature of capitalism.

Moliere’s play Le Malade Imaginaire, upon which the text for this performance is based, was his final work, written at the height of his fame. The history of the play’s creation includes a remarkable story, often repeated in theatrical lore, and worth doing so again:

Moliere had himself endured a lengthy illness by the time he came to write Le Malade Imaginaire in late 1672. In fact when I say lengthy I’m sugar-coating it. He suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, which he may well have been carrying for most of his adult life, and certainly he had been forced to take extended time off as early as 1667. The ridicule of doctors was a theme that Moliere returned to repeatedly throughout his career. While it is true that the pompous but ignorant Dottore, is a stock-character of the Commedia Dell’arte – the genre on which Moliere’s comedies are based, it seems unlikely that this alone explains his pre-occupation with the subject. His mother had died while he was still a boy, and her demise was callously and incompetently dealt with by a series of doctors, and of course he himself had been a patient for many years and of many doctors, without ultimately deriving much benefit from the experience. But this play goes further than the ridicule of doctors – who were at the time notoriously unreliable. Here Moliere’s critical focus is on Argan, their patient. This may well have been for little more reason than the fact that Moliere had by this time been repeatedly and unfairly smeared by his rivals at court as a hypochondriac himself. Moliere regularly performed the lead roles in his comedies himself, and accordingly he was the first actor to play Argan. There is an overt self-referential element in the play, and his focus on the patient was in fact a parody of his enemies’ criticisms of himself. However the self-referential took a turn for the tragic and in fact became legendary on the night of the fourth performance of the play. Moliere began haemorrhaging and coughing blood whilst onstage performing. He got through the performance, but died a couple of hours later.

It’s this partial focus on the hypochondriac patient that makes Le Malade Imaginaire an interesting piece for contemporary production, but it also presents some particular challenges. The play is substantially full of contemporary resonance. The self-indulgent patient, over-eager for medications, drugs and treatments of all kinds is perhaps a more timely subject for satire now than ever before, and stories of quack doctors (whether on the internet, television, or even sadly in a Queensland hospital) abusing their position of trust with their incompetence or greed, emerge on a regular basis. However the play does pre-suppose a society in which medicine as an entire profession is deeply suspect, where putting yourself in the care of a doctor is to risk your life as well as your fortune. It’s a world where the prevailing view at the time was that the best way to train a doctor was to have them study invented theories, rather than the human body itself. In short its satire of the medical profession is in part quite dated.

I selected this free adaptation of the play by Richard Bean, under the title The Hypochondriac because it subtly but thoroughly re-imagines the situations in the play to shift the focus from the doctor to the patient, and from the social manners of 17th century Paris, to the underlying, rampant desires and fears that Moliere has written into the characters.