Mr Bailey’s Minder

Griffin Theatre Company and Riverina Theatre Company

Sydney 2004

Wagga Wagga 2004

National Tour 2006

Winner – 2003 Griffin Award for Best New Play

Winner – 2006 Drover Award for Best Touring Production

Shortlist – 2004 NSW Premier’s Literary Award for Best New Play

“Director Christopher Hurrell keeps the energy high but wisely does not hurry the action. Time is taken to exploit comedy in awkwardness or to allow a shift to a darker mood.

Those final moments … mix excruciating irony with a beautifully realised glimpse of forgiveness. It is a fitting highpoint to conclude the premiere of an excellent new Australian play.”

SYDNEY MORNING HERALD

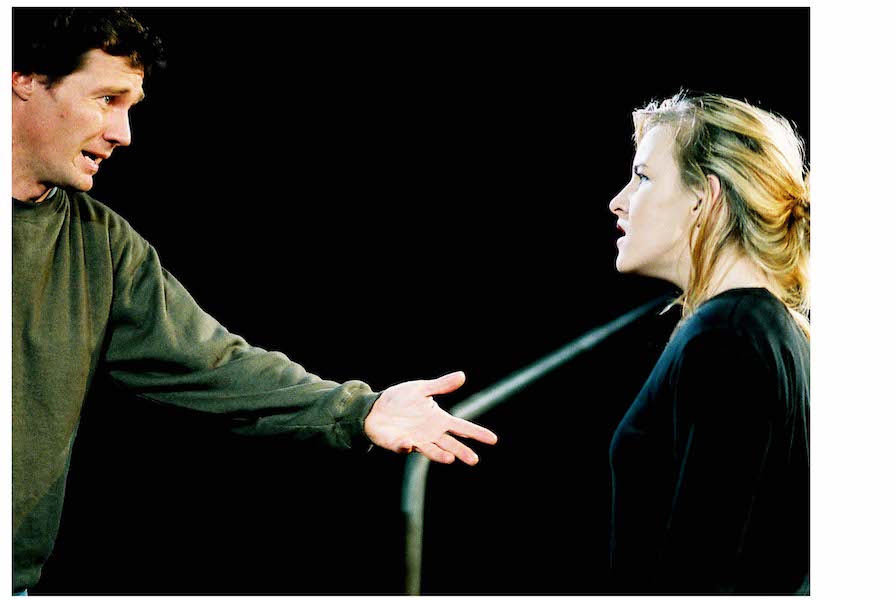

Therese

Kate Mulvany

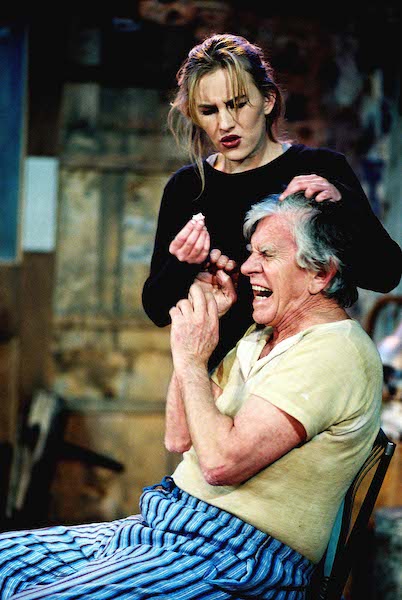

Leo Bailey

Martin Vaughan

Margo

Victoria Longley

Karl/Gavin

Andy Rodoreda

On tour in 2006, Kate and Andy were joined by:

Jonathan Elsom as Leo

Kirrily White as Margo

Director & Dramaturg

Christopher Hurrell

Assistant Director & Choreographer

Velalien

Production Designer

Jo Briscoe

Lighting Designer Stephen Hawker

Sound Designer

Basil Hogios

Co-Production Managers

Glenn Dulihanty & Liam Fraser

Stage Manager

Ned Matthews

Assistant Stage Manger

Velalien

Design Assistant

William Goodes

Set Construction

Justin Green

Introduction to the Published Edition

by Christopher Hurrell

“It’s like Leo can see the specialness inside a thing so when a person looks at the painting they can see it too.

---

Leo Bailey is like a sac of poison in my belly. Toxins leak out into my system if I’m not vigilant.”

How can the two men described above be one and the same? This is the conundrum that haunts Mr Bailey’s Minder.

The history of art is full of anecdotes about tortured artists destroying their own lives and those of others; tormenting their family and friends with temper, capriciousness and cruelty. In short, stories of great artists failing to be even mediocre human beings.

How do we reconcile this with the fact that the artist’s gift is the ability to ‘see the specialness inside a thing’—a talent that would seem to be synonymous with the ‘emotional imagination’ necessary for compassion?

Leo Bailey is Australia’s greatest living artist. However, this is not a play about the nature of art, or of artists, though observations on those two subjects feed into the play’s heart. Rather, Debra Oswald poses not a passive ‘How can this be?’, but an active ‘How can we accept this?’

Mr Bailey’s Minder is a play richly infused with the remarkable spirit of its author: compassionate, insightful and ethical. Debra’s ethic is both demanding and forgiving. On the one hand, the play seems to say there is no excuse for behaviour that damages those who share the earth with us. On the other hand, it reassures us: if we find this challenge difficult to meet, we should take heart because even those blessed with a genius for seeing and understanding others often find it almost impossible.

The theme of healing damaged souls is a recurring one in Debra’s work and it is one which is central to Mr Bailey’s Minder. It is an essential element to the theatrical experience she seeks to create. The ultimate ambition of a play such as Mr Bailey’s Minder is not only to tell a story of souls healing together. Through the power, human complexity and catharsis of that story, it seeks to create an experience that is spiritually restorative for its audience. Critics often struggle to define the experience of a Debra Oswald play. Perhaps the most apt, simple description of her work came from the Age’s Helen Thomson, who described it as containing ‘authentic optimism’. Debra constructs dramatic situations loaded with genuine, complex human suffering and shortcoming, and then finds credible, difficult resolution. It seems to offer us real hope that even the darkest passages of our lives can be successfully navigated; that it’s never to late to find healing. You may be stuck with the scars, and things will never be perfect, but rehabilitation is possible and worth seeking.

Therese struggles with self-loathing. She brings into Leo Bailey’s house resilience, an experience of deprivation and, above all things, ignorance. She has no idea who Leo Bailey is. The fact that he’s famous and talented means nothing to her. Thus from the outset, Leo is unable to find the weak-spot in her that he has found in perhaps every other person he’s met in at least a quarter of a century.

It doesn’t take him long to locate a weakness in Therese, but it comes with a surprise: an aggressive, instinctive defence mechanism. No one is going to inflame the wounds of her self-doubt without a sharp jab in return.

Therese, unlike Leo, has a lifetime’s experience of true deprivation: imprisonment, betrayal, failure. Yet she possesses a resilience and strength that leaves Leo for dead. She responds to her extensive, tangible suffering with determination to do better. Her example reveals that the ‘artist’s tortured inner life’ justification is a childish indulgence.

Leo’s experience of deprivation is much more recent and unfamiliar to him. He’s outraged to find, through age and deterioration, that he is no longer at unbridled liberty to do as he pleases. ‘I wanted go out! Out’, he squawks petulantly, early in the play. Faced with someone infinitely stronger than himself, he is nonplussed. He begins to capitulate. The strange combination of real care with steadfast refusal to indulge him is the first decent medicine offered him after years of physical and mental sickness.

And so the healing begins. Therese eloquently describes the feeling of debilitating shame and Leo regains a little of the self-awareness that deserted him years ago in a storm of sycophancy, alcohol abuse, creative frenzy and self-obsession.

THERESE: Some memory oozes up and eats away at your guts, eh. You know what I think about sometimes? When I’m in the shower, I tip my head back and I let the water run down my face and neck and I imagine if the water could wash it all away…

LEO: The shame.

THERESE: Yeah. Wash away every bad thing I ever did. Start again, clean.

Two more damaged souls inhabit the play. Leo’s daughter Margo is a complex figure, who surprisingly turns out to be the play’s emotional centre. She is responsible for managing Leo’s life, and she does so with cool detachment. It’s she who hires Therese to care for him. Margo

is also responsible for sending the tradesman Karl into the house, to remove one of the few remaining art works of value. Like Margo, but for totally different reasons, Karl is one of life’s ‘stayers’. Their own wounds have left them suffering from opposite deficiencies. Margo is no longer able to see the good in others, Karl no longer able to see the bad. But it’s the staying quality in both these characters as well as in Therese that holds the four characters together to redeem each other.

The silent character in this play is the house. Leo doesn’t live in a real house—rather a shack pulled together from his life and art. The house, and the remnants of the art it contains, also play their part in the healing. Therese’s early success with Leo leads them out of the tumbledown prison and, by chance, into one of the temples of capitalism in the city centre, where Therese for the first time comes face-to-face with one of Leo’s great works adorning an imposing corporate foyer:

THERESE: It’s like there’s a light inside the painting shining directly on me, filling me up, sending an electric charge through my blood into every tiny cell of me.

The play binds belief in the redemptive power of art into its human core, but refuses to mythologise it or its creators. It tells us that talents and abilities—of any kind—are immaterial. The difficult responsibility of caring for fellow-souls is one we all must struggle with in order to honour our own humanity.

As director of the first production of a new play, one of the first challenges I face is to establish its performance style. It is customary to think of Debra purely as a practitioner of Australian Naturalism. This, however, is inaccurate and misses the point of Debra’s work. While her plays are largely naturalistic in form, the sensibility that governs them is innately theatrical. Debra herself is the first to proclaim ‘I’m not a stylist’, but it is instructive that her own theatrical hero when she first began writing plays as a teenager was Joe Orton, with his heightened, radical, subversive comedies.

Debra’s work exists as much in a tradition of wild theatrical comedy as any other. The sensibility comes from, say, Molière, bequeathed to her via Orton and, more locally, the knockabout comedy of the Australian New-Wave, which she experienced first-hand as part of Nimrod’s earliest audiences at Sydney’s tiny Stables Theatre, more than thirty years before this play would premiere in the same theatre. She describes sitting in the front row as a child, entranced by Reg Livermore, as the experience which called her to the theatre.

And so the piece exists in an intrinsically Australian theatrical world, inhabited by warmth and roughness, empathy and absurdity, broad humour and searing pathos.

“Like her character Leo Bailey, playwright Debra Oswald reveals the luminous inner beauty of ordinary men and women emotionally scarred by life.”

Sydney Morning Herald

“Debra Oswald finds the goodness in lonely, damaged people and then lets them find each other. There is so much emotional truth here and the small triumphs of these characters are so hard won, that the result is inspirational - so simply told that it assumes some of the qualities of a parable. The script and Christopher Hurrell's production are full of comedy.”

The Australian

“Director Christopher Hurrell allows time for the unspoken to settle without threatening the comic pacing and dramatic thrust.”

Sunday Telegraph

“Debra Oswald's wonderful new play grapples with how much latitude we're prepared to give artists we consider to be blessed with some kind of genius. It also explores the separate journeys of three individuals committed to creating a place where they can belong.”

Variety