Christopher’s doctoral thesis, “Hear My Soul Speak” – Finding Prospero in the Verbal Music of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, of a scholarly narrative in dialogue with documentation of practice-research laboratory work with professional actors and specialist voice practitioners; and the communication of findings through a multi-media performance for actors and singer working both live and through digital transmission.

This thesis investigates the capacity of the verbal music of Shakespeare’s poetry in The Tempest, to suggest an account of the complexity, irrationality and nuance of human experience in the character of Prospero, through its somatic impact on the actor. In Shakespeare’s “verbal music”, Peter Brook sees, beyond “concept and image … an infinitely powerful further dimension which comes from sound”. The research question has its origins in my enquiry as a stage director into how rehearsal process might best sensitise actors to the presence of this verbal music and orient their process towards a relationship with it.

”Concept is there, but beyond concept is the ‘concept brought into life by image’, and beyond concept and image is music – and word music is the expression of what cannot be caught in conceptual speech. Human experience that cannot be conceptualised is expressed through music. Poetry comes out of this, because in poetry you have an infinitely subtle relationship between rhythm, tone, vibration and energy, which give to each word as it is spoken concept, image and at the same time an infinitely powerful further dimension which comes from sound, from the verbal music.

Peter Brook

”Even Prospero, its most dominant and fully displayed figure, is curiously opaque. The theatre audience may be privileged to overhear his soliloquies and asides. It watches him in his dealings with a spirit world entirely unavailable to all the other human characters of the play, even Miranda, about it is never really allowed to penetrate his consciousness.

Anne Barton

No protagonist in Shakespeare has proven so consistently mystifying to readers and audiences, in both personality and intentions, as Prospero. Past generations, satisfied to see in this ambiguity the representation of a divine mystery—a Prospero somehow above humanity—were content to trust his claim to a divinely sanctioned, supernatural authority, and frequently to perceive in that authority a meta-theatrical avatar of Shakespeare himself. Twentieth century performance and criticism reacted violently against this hegemony, and as a result no protagonist in Shakespeare has undergone such an interpretive reversal as Prospero. Once a benign, serene, dispassionate lawgiver, he became instead a corrupted, violent oppressor and more recently a despairing neurotic, fighting his own frailty and an overwhelming sense of both guilt and victimhood.

This apparent elusiveness of authorial intent regarding the persona of the protagonist is used as a locus to explore not only the implications of auricular effect in the complex poetry of Prospero’s utterance—amongst the most knotted, ornate and ethereal language in the Shakespearean canon—but also to consider the broader questions raised regarding the theatrical language of the play, including its use of music, the mode of representation of personality it adopts and the Early Modern paradigms of individual identity which inform it.

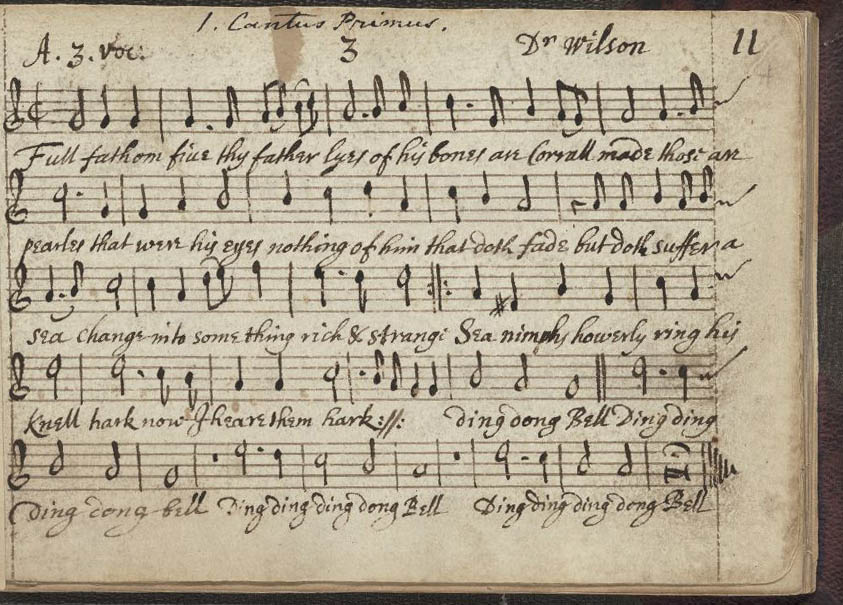

The original music, by Robert Johnson, to Shakespeare’s “Full Fathom Five” in The Tempest

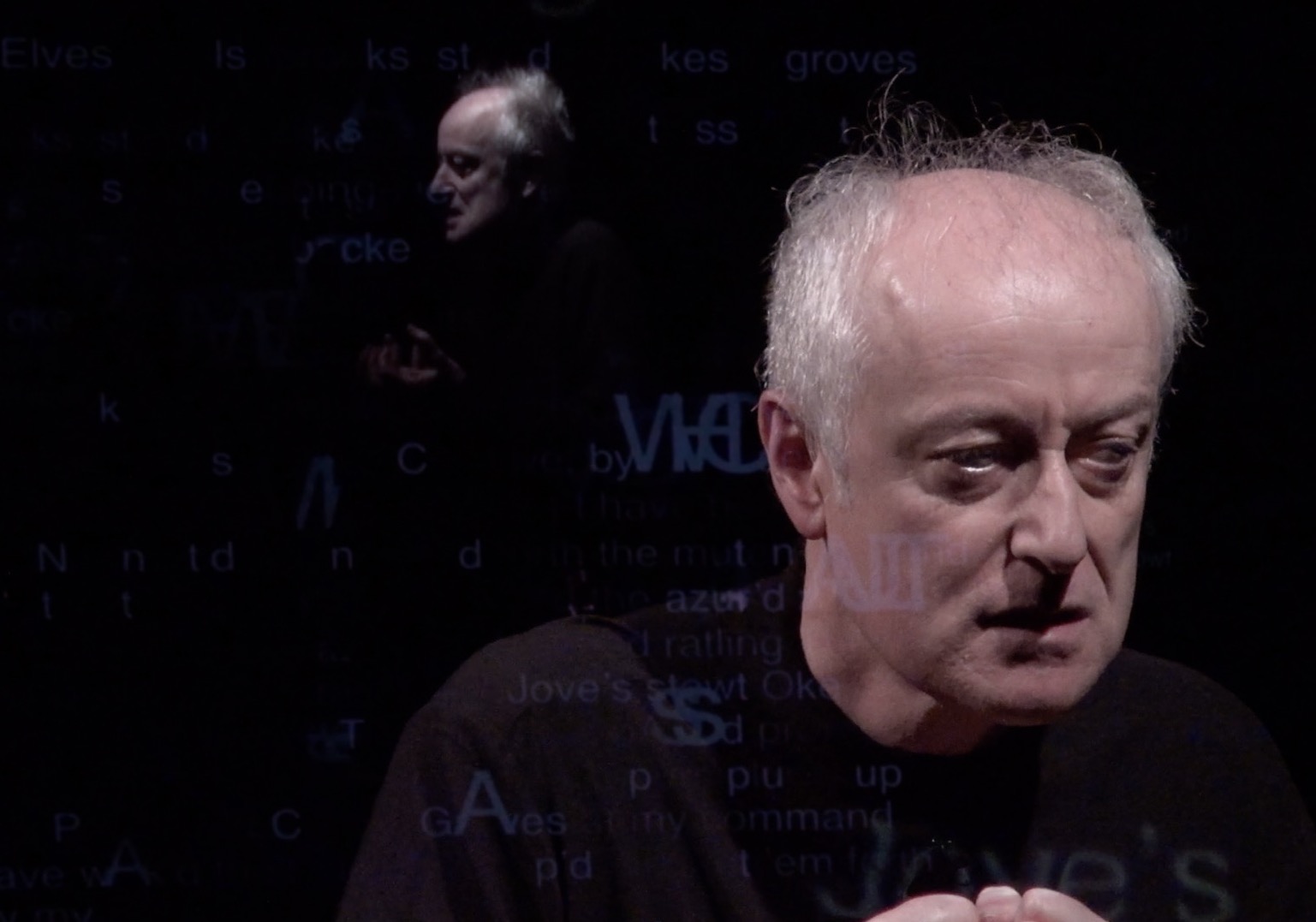

Gerrard McArthur in Hear My Soul Speak.

Based on The Tempest by William Shakespeare.

Extensive practice research laboratories, leading to a performance, were conducted in collaboration with the principal co-informant to the practice research: the actor and director Gerrard McArthur. The performance, which explicates both the process adopted in the laboratories and the view which emerged of Prospero’s persona and its function in the play’s dramaturgy, forms the conclusion to this thesis.